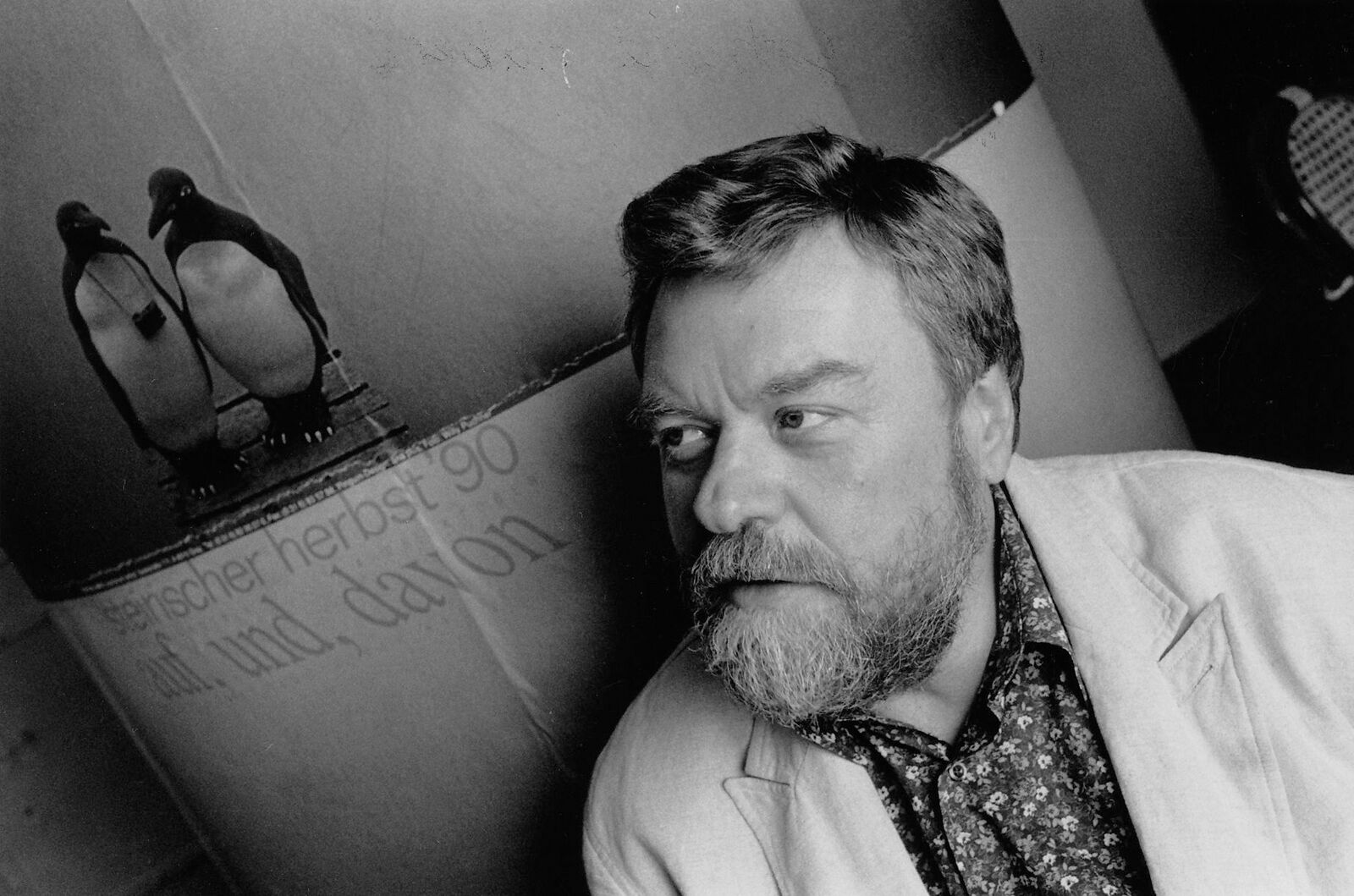

Horst Gerhard Haberl

Roman Haubenstock-Ramati, Amerika (1962/64), opera, Oper Graz, 1992, photo: Peter Manninger

Générik Vapeur, Bivouac (1988), performance, at Grazer Combustion, corner of Sporgasse and Hofgasse, Graz, 1993, photo: stefanharing.com

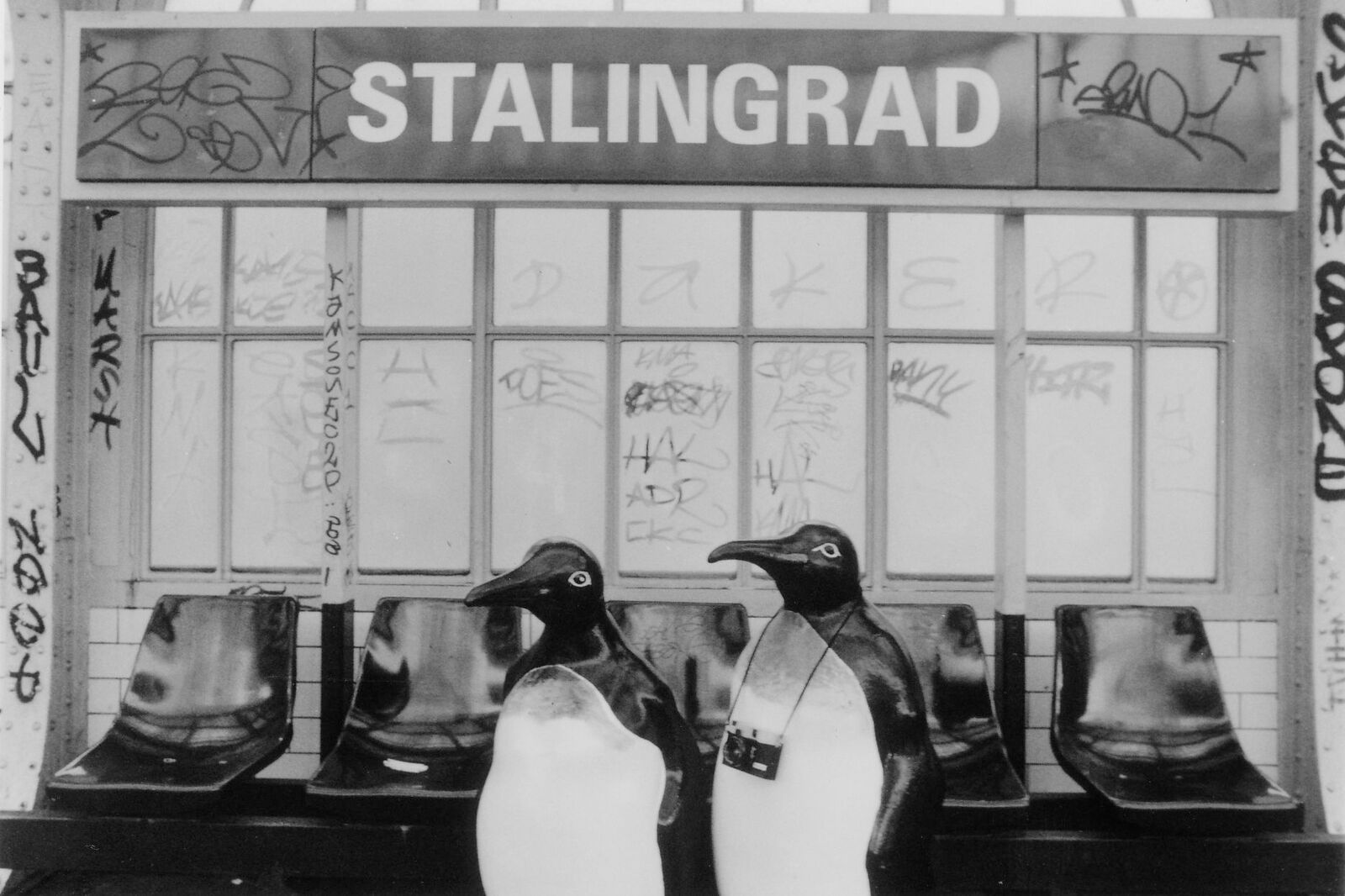

Die Sehnsucht der Pinguine—Eine Bilderreise (penguin design © anaplus), poster motif for steirischer herbst ’90; photo: courtesy of the artist

Botho Strauß, Angelas Kleider (1991), play, directed by Leander Haußmann, with Götz Argus, Schauspielhaus Graz, 1991, photo: Peter Manninger

Horst Gerhard Haberl, poster for steirischer herbst ’94, Erzherzog-Johann-Allee, Graz, 1994, photo: stefanharing.com

Pierre-Alain Hubert and Alfred Pokorny, Die Funken fliegen („Hôtel des étincelles“), pyrotechnic performance and fireworks, at Grazer Combustion, Kasemattenbühne, Graz, 1993, photo: stefanharing.com

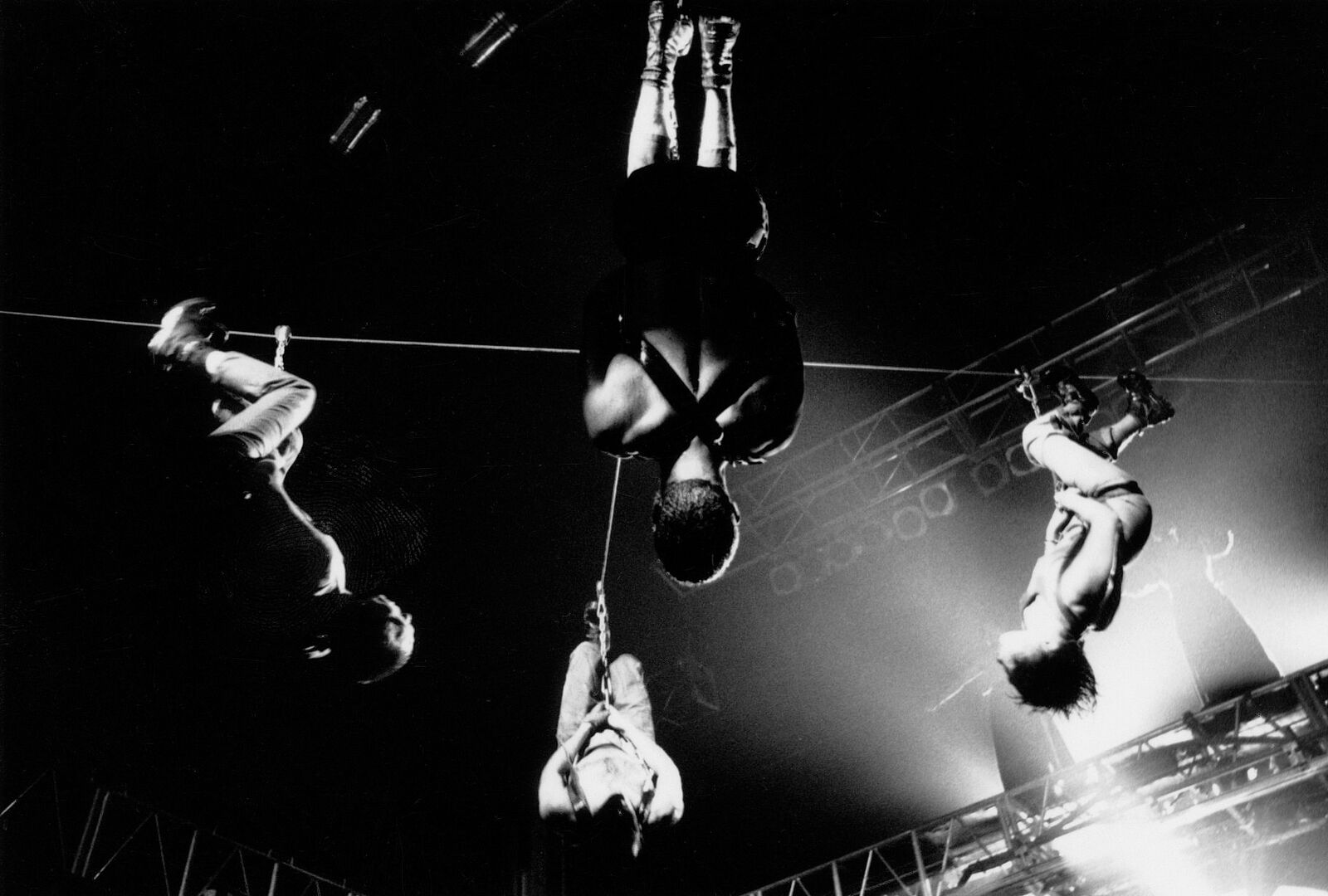

La Fura dels Baus, Noun (1990), performance, Waagner-Biro-Halle, Graz, 1991, photo: stefanharing.com

Claudia Pöllabauer, herbstbar 1 (1995), intervention, Lichtschwert in front of Oper Graz, 1995, photo: steirischer herbst archive / Philipp

MANUELA, evening’s dancing, at JE T’AIME. The Love Song, Kammersaal Graz, 1993, photo: steirischer herbst archive

Christoph Schlingensief, Hurra, Jesus! Ein Hochkampf (1995), play, with Joachim Tomaschewsky, Mario Garzaner, and Steffen Höld, Schauspielhaus Graz, 1995, photo: Peter Manninger

1990–1995

Following a battle in Austrian cultural politics over who would succeed Peter Vujica, Horst Gerhard Haberl ultimately prevailed over the artist and media theorist Richard Kriesche. As a member of the Program Advisory Board since 1969, Haberl, like Vujica, had been closely connected with steirischer herbst since its first years. A former employee of Wilfried Skreiner at the Neue Galerie, Haberl had moved to the Graz-based shoe company Humanic in 1969, where he created the innovative advertising slogan “Franz,” and was later art director and head of advertising of the company-owned Galerie H.

The same year, Haberl established the interdisciplinary artists’ group pool with Richard Kriesche and Karl Neubacher, and, in 1974, the poolerie action space. As a curator, Haberl was responsible for various spectacular steirischer herbst exhibitions that were international and intermedial in their orientation: Körpersprache—Bodylanguage in a tent in the Volksgarten in Graz (1973), Der Amerikanische Video-Underground (The Video Underground in America; part of trigon 73: Audiovisuelle Botschaften [Audiovisual Messages], 1973), Kunst als Lebensritual (Art as a Life Ritual) at the poolerie (1974), and Die Barocken Wilden (The Wild Ones of the Baroque) at the Alte Galerie and Mythen der Zukunft (Myths of the Future) at various locations in Graz (1983).

As the second artistic director, Haberl looked for a conceptual linchpin for steirische herbst in the sociopolitical context of contemporary art and its expanded concept of art. In cooperation with the philosopher Peter Strasser—and with Werner Krause (theater, literature) and Cathrin Pichler (visual art, as of 1992) on the program committee—he conceived a “sort of corporate philosophy” for steirischer herbst ’89, which would redefine the presentation and discussion of cross-boundary phenomena in art and the cultural behavior of the 1990s.1 A “festival of contemporary culture” was to replace the concept of the avant-garde of the 1960s and 1970s, which had become obsolete, and the fatigue resulting from the innovations of the 1980s. “The ideals of the countermovement are diligence, precision, interpretation, and the development of new fields of relationships, resulting in the establishment of new forms of cultural behavior” (program booklet, 1990).

steirischer herbst was to provide a place for encounters with “nomadic” strategies in art at the end of the postmodern age. Haberl positioned the years of his artistic direction, based on Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, under the umbrella concept of a “nomadology of the 1990s,” which linked the individual overarching themes with one another. He simultaneously proclaimed a paradigm shift for the next decade. “With the nomadology of the 1990s, steirischer herbst intends to span a bridge to the culture of mobility, as one possible third path besides the avant-garde and the postmodern,” as Haberl wrote in the program booklet for 1990.

This reorientation was accompanied by an increasing globalization and the resulting nomadization of the art world in the 1990s, as reflected in the establishment of innumerable new biennials all over the world. But even more than globalization or global refugee movements, Haberl and Strasser were interested in “new aspects of an intellectual mobility, a lived interdisciplinarity, and a nomadizing sensibility,” which “on the one hand, reflect the sociopolitical context of the contemporary behavior in art and culture, and, on the other, are oriented contrary to the either/or fixation of disparate disciplines in art, science, technology, politics, et cetera.”2

To provide a foundation for the theoretical superstructure of a principle of nomadic thinking, Haberl and Strasser initiated the Herbstschrift as a literary forum for the “nomadology of the 1990s.” Authors such as Vilém Flusser, Peter Sloterdijk, Adolf Holl, Franz Schuh, Thomas Macho, Peter Jirak, and Peter Strasser contributed essays to the first volume, herbstbuch eins.

The first guiding theme during Haberl’s time as artistic director was auf, und, davon (Up, and, Away). The idiosyncratic punctuation referred to “the reflexive, to a moving-away-from, to possibilities that make it possible to hope again”—very much in the spirit of the keynote speaker, Vilém Flusser: “For nomads, ownership of concepts is madness. And for settled individuals, undefined wandering is senseless rambling. However, we no longer see a nothingness, but rather a concrete (if also invisible) field of relationships.”3 Corresponding to the nomadic principle of a tent, Haberl organized an architecture competition for a mobile event hall as a “symbol of cultural and intellectual mobility” at the Alte Remise in 1990.

Under Haberl’s artistic direction, with Johannes Frankfurter as dramaturge, there were spectacular theater premieres by Botho Strauß (1991), Werner Schwab (1992, 1993), Urs Widmer (1993), and Christoph Schlingensief (1995) and an opera premiere by Beat Furrer (1994). In addition, there were art performances such as the monumental sculpture Lichtschwert (Light Sword) by Hartmut Skerbisch (1992) and events such as Grazer Combustion (1993)—a “controversial cycle at, in, and around the Schloßberg in Graz, in the form of an exhibition staging and a concentrated series of performances,” as well as a pop song revue. Particular attention was given to the perception of steirischer herbst outside of Graz with project series such as the Mürztaler Werkstatt, the Hör-Fest Steinach, the Schreams cultural initiative, or the Kult-Ur-Weg-Pischelsdorf.

Haberl’s time as artistic director ended in 1995 with the overarching theme “art is over, the game goes on,” which summarized his tenure in a suggestive way. Two years before, in cooperation with Peter Strasser, he had developed a concept for a content-related restructuring of steirischer herbst, which related to the planned construction of a new Kunsthaus in Graz and based on the insight that “the limited duration of a festival is not sufficient for presenting future-oriented aesthetic issues or corresponding interdisciplinary objects of research and making them legible.” However, the concept failed, according to Haberl, due to the partisan pragmatism on the regional level.

The trigon biennale also took place for the last time in 1995. It was no longer relevant due to the departure of Wilfried Skreiner, the increasing interdisciplinary orientation of the festival, and the political upheavals that followed the dissolution of Yugoslavia.

Horst Gerhard Haberl’s departure is marked by a note of bitterness. Peter Strasser, a leading member in his advisory council, commented, “If I had not been aware at the time of the baseness of which so-called civilized people are capable—I was able to experience it then.”4 According to Strasser, Haberl had been calumniated for such a long period of time “that the media started to enjoy [reporting] on what they called ‘the outdated festival.’”

- 1

- Horst Gerhard Haberl, “Das nomadische Prinzip,” in Nomadologie der Neunziger: steirischer herbst Graz 1990 bis 1995, ed. Horst Gerhard Haberl and Peter Strasser (Ostfildern: Cantz, 1995).

- 2

- Haberl, “Das nomadische Prinzip,” p. 17.

- 3

- Cited in Haberl, “auf, und, davon,” p. 5.

- 4

- Peter Strasser, “Der Höhepunkt H.G.H.,” in herbstbuch: 1968–2017, ed. Martin Behr et al. (Vienna: Styria, 2017), p. 189.

Bio

Photo: Christian Jungwirth

Horst Gerhard Haberl

(1941, Graz)

Exhibition and project curator, arts editor, editor and author of numerous publications and television features (ORF) on contemporary art

Studied art history and philosophy

1967–73 Collaborator and Curator at Neue Galerie Graz

1969–84 Art Director and Director of the “Future Department” at Humanic AG, Graz/Vienna (afterwards Art Consultant until 1995)

1970–76 Founding President of the artists’ group pool, Graz/Vienna, Coeditor of the arts magazines pfirsich and pferscha

1973–84 Founder and Director of the Interdisciplinary Communication and Exhibition Space for Contemporary Art galerie H, Graz

1978–80 Artistic Director of the International Biennial Exhibition of Graphic and Visual Art at Wiener Secession

1984–88 Art critic and Director of the culture pages at Kleine Zeitung, Graz

1990–95 Director of steirischer herbst

1992–2004 Professor for Art Education and Design Theory at Hochschule der Bildenden Künste Saar, Saarbrücken (HBKsaar)

1993–2001 President of HBKsaar

Awards

2006 Hanns-Koren-Kulturpreis des Landes Steiermark

Publications (selection)

Körpersprache/Body-language (pfirsich 9/10). Graz: Pool, 1973.

Kunst als Lebensritual / Art as Living Ritual (pfirsich 12/14). Graz: Pool, 1974.

Friederike Pezold (pfirsich 15). Graz: Pool, 1975.

Expansion: Internationale Biennale für Graphik und Visuelle Kunst. Vienna: Verein Zur Durchführung der Internationalen Biennale für Graphik und Visuelle Kunst, 1979.

Die barocken Wilden. Alte Galerie am Landesmuseum Joanneum. Graz: Droschl, 1983.

„Kunst als Kommunikationsstrategie“. Kunstforum International 87 (1987), p. 242 f.

Ed. with Peter Strasser: Nomadologie der Neunziger: steirischer herbst, 1990 bis 1995. Ostfildern: Cantz, 1995.

Festival editions

Retrospective

Retrospective